Several years ago, I served on the board of directors of a pair of Atlantic City, New Jersey hotels. It was in Atlantic City that Charles Darrow created the board game Monopoly in 1933. As a child I loved to evaluate my financial skills against my peers and even some adults. The game taught me the joy and dread of owning my own property. While Monopoly had a laissez-faire structure, there was always the chilling specter, presiding over each roll of the dice of some Boardwalk Big Brother, who had the power to tax me, seize my assets or even send me directly to jail.

One of the many things I have learned from the late Joseph Sobran was the name of Igor Shafarevich’s and his powerful essay, In Our Past and Future, which reminded the free world that communism had marked private property as one of its three targets for destruction.

The Declaration of Independence enumerates only three fundamental rights. They include the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The last is a generic term that Thomas Jefferson substituted for John Locke’s estate, more properly known as private property. These rights are not contrived, such as the right to an abortion. Nor are they a privilege, such as the right to drive a car. They have been gleaned from the book of nature and written in the souls of every human being at the moment of conception.

Private property is the tangible glue that holds the trio together. Without property ownership, life and freedom are more difficult to maintain. An individual’s ownership of material possessions, such as land, money, jewels, and machines, secures the freedom to live, move and earn. Communists have always recognized this as a natural fact. This is why they have sought to deprive humans of as much of their property as they could through revolution, high taxation, and redistributive programs.

One man who foresaw the deleterious effects of the communistic approach was political economist, Frederic Bastiat. Born in 1801 in Bayonne, in Northwest France, Bastiat spent his childhood on a farm in Mugron. Orphaned at age nine, he spent his formative years, reading, writing, and thinking about the ills of post-Napoleonic France. Some early business experience combined with his studies in mathematics, natural history, mechanics, and several foreign languages taught him that the deadly hand of government control was a barrier to economic prosperity.

Bastiat’s studies in history and philosophy taught him that the secrets of prosperity, what Americans call the pursuit of happiness, lay in a trio of conservative values, which included limited government, personal responsibility and faith in the Creator. Bastiat believed that there was a natural harmony to the social order that emanated from the free exchange between human beings, hoping to supply their unlimited demands in a world of limited resources.

He believed the absence of outside interference with freedom and its corollaries of private property and competition would provide a steady progress for the material well-being of all. Elected to the French National assembly in 1848, Bastiat became a stern opponent of the revolutionary furor that was escalating all over Europe. France was in bloody turmoil. Marx and Engels were publishing their historic tract The Communist Manifesto as the civilized world seemed headed for collapse. Not since the French Revolution had property rights and personal liberty been so endangered.

In just a short period of time, Bastiat produced a library of perceptive work on free trade, money, and domestic markets. His most lasting contribution was a lengthy pamphlet, simply entitled The Law. While most political writers, such as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, have held the law as having derived from a social contract with a paternalistic sovereign, as an arbitrary convention defining right and wrong, Bastiat wrote that, life, liberty, and property do not exist because men have made laws.

On the contrary, this trinity of natural rights predated the law. Men have had to make laws to protect these natural rights. The source for all this was man’s human nature. The Creator had implanted in each and every human being the desire to be free and to own property.

To Bastiat the natural condition of a man was privation. If a man did not work, his only other choice was to live off the labors of others. To him this was a form of self-perpetuating slavery, not unlike the welfare system of the last three-quarters of a century of American history. By living off the productivity of other people who were not granted any choice in the matter, they formed a parasitic class that drained the vitality from any economic system.

Unrestricted freeloading undermined all the basic principles of charity, honesty, and natural law. Big Government to Bastiat was the great fiction through which everyone endeavors to live at the expense of everyone else. No society can prosper with this as an integral part of its political economy. Bastiat’s ideas on big government segue nicely with historian Lord Acton’s famous maxim Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

To Bastiat any law that negatively infringed on life, liberty or private property was not proper law, but legalized plunder. He realized that this was a constant temptation as man’s fallen nature leaned toward wanting to achieve his objectives with as little effort as possible. Sobran constantly reminds us to Look at the law and see if it does for one man at the expense of another what would be a crime for the one to do to the other himself.

In other words, Big Government often engages in the criminal conduct which it is empowered to prevent. This parallels the thinking of St. Thomas Aquinas. In his Summa Theologica, he raised the question Is it possible for robbery to take place without sin? He concluded: it is no robbery if princes exact from their subjects that is justly due for safe-guarding the common good. But if governments tax excessively, it is robbery and therefore sinful.

Bastiat was a faithful Christian who converted to the Catholic faith in Rome, shortly before his death from tuberculosis in 1850. His faith in God was at the heart of much of his thinking. We believe in liberty because we believe in the harmony of the universe that is in God. To tamper with man’s freedom is not only to injure him, but also to strip him of his resemblance to the Creator.

The Progressive period (1870-1920) in American history was the era that witnessed the most rapid growth in the kind of government intrusion Bastiat had warned against. It was an era, marked by an explosion in wealth, which had largely accrued to the business giants of the post-Civil war era.

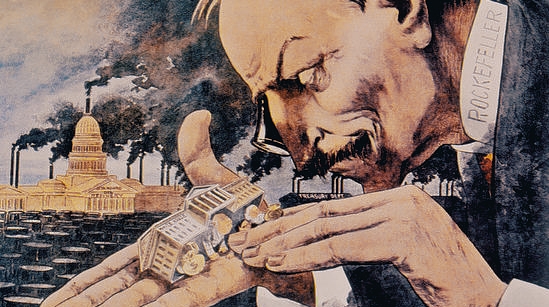

The Progressives called them robber barons, a pejorative term used to describe these legendary tycoons, such as the Rockefellers, Carnegies, Morgans, Vanderbilts, and Astors. Their ostentatious display of wealth and luxurious lifestyles chaffed the conscience of an outraged amalgamation of ministers, educators, and politicians. The widespread existence of poverty amid a Gilded Age of excess inspired Progressivism with its fondness for socialist ideals and methods. It is a scenario that still continues today.

Books like Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, published in 1888, in the Rip Van Winkle genre, assailed the lavish instances of excessive individualism. Bellamy’s book, which read like a socialist tract, resonated with a society that had lost its respect for unfettered individualism.

Progressivism reflected the emerging Social Gospel, which urged people to save their souls by helping those ravished by a raging industrialism. By 1900 American society had lost its faith in the raw individualism of its formative years and had adopted a new collective spirit that emphasized group solidarity over individual achievement.

Progressivism drew its greatest inspiration from a book by journalist, Herbert Croly, entitled The Promise of American Life. The founder of the leftist journal, The New Republic, Croly believed that there were two diametric forces at work in American society. The first was the Hamiltonian notion of big business, normally associated with aristocracy and special privilege. The Jeffersonian ideal favored the laissez faire philosophy of small government. It stood for equal rights and opportunities, democracy and the small farmer.

Croly called for a new orientation, which might be called a political miscegenation, among progressives, whereby Jeffersonians abandoned their fear and hatred of big government, while Hamiltonians adapted their means to foster Jefferson’s democratic ideals. It was a political marriage, arranged not in heaven, but in Croly’s utopian mind. Government had assumed an unprecedented role as an active force in the betterment of the individual lives of its citizens through grants, subsidies, programs, and other federal philanthropies.

Progressivism was an ideological watershed, which demarcated a radical change in the government’s perception of its powers and duties. This unnatural political marriage changed the relationship between government and its citizens forever. Progressivism rapidly advanced with the arrival of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson on the political scene.

The Republican Roosevelt used Croly’s book to formulate much of his own thinking. He recognized that government activism required new levels of fiscal appropriations. He believed that the man of great wealth owes a peculiar obligation because he derives special advantage from the mere existence of government.

Theodore Roosevelt believed that this debt should be recognized not only in the way the wealthy man lives but also by the way in which he pays for the protection the State gives him. To the astute observer, the word protection is noteworthy. In the twenties and thirties, it served as a euphemism for the rise of organized crime, which extorted millions from the public for protection. This lends credence to Bastiat’s view that government was legalized plunder.

The political skills of Franklin Roosevelt and the progressive philosophy of his New Deal, as well that of his philosophical heirs in the New Frontier and the Great Society, turned this marriage into a family tree of entitlements that has enmeshed the political economies of the next several generations into a system of personal dependency. Its confiscatory economic policies erected a lasting fortress in which the federal government served as the Guarantor State,not for the pursuit of happiness, but for its guarantee. One can only surmise what financial havoc and limitation of property rights will occur when the bill comes due for a three-quarters of a century of wanton financial profligacy from years of Social Security, Medicare, Prescription drug payments and eventual universal health care.

A direct result of the progressive thinking of the Roosevelt cousins has been the country’s unfathomable tax code. How many Americans know the origins of its twin pillars, the graduated income tax, and the estate tax? Most Americans probably think they are the work of democratically oriented thinkers, such as Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, or even Alan Greenspan. Both came from Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto.

To pay for all this social engineering, the government needed a coercive collection agency. The Internal Revenue Service was founded in 1862 to collect taxes to help pay for the Civil War. Congress repealed it 10 years later. Congress revived the income tax in 1894, only to have it declared unconstitutional the following year. In 1913 the states ratified the 16th amendment which gave Congress the constitutional authority to enact an income tax.

The initial tax was just 1% on personal incomes above $3,000 and a surtax on all income over $500,000. Since then, the tax rate has fluctuated from 91% in the Kennedy years to 28% during the early Reagan years. Before the 16th amendment, the only constitutional tax powers were tariffs and state assessments. Even with tax cuts, the top five percent of American taxpayers pay half of the federal income taxes. This drastically contrasts with the religious idea of tithing, which only asks, not demands, just 10% of their members’ earnings.

The IRS rules through intimidation. Nothing is more frightening than having to undergo a tax audit. While the tax structure is supposed to be voluntary, taxpayers should never forget that it is backed up by the full extent of the nation’s tax laws, which can result in severe fines and even prison.

Two classic works expose the IRS’s historical predilection to unnerve the people it allegedly serves. Shelley L. Davis’ Unbridled Power: Inside the Secret Culture of the IRS, (1997), and Charles Adams’ Those Dirty Rotten Taxes, (1998) portray a government agency, more secretive than the CIA, which has dominated its public citizenry with virtual impunity. It did not take Davis, the agency’s official historian, long to realize that the IRS was not a gang of streetcorner Santa Clauses.

Since its inception, presidents have used the unbridled power of the IRS to harass, threaten, punish and even destroy businesses, unpopular political advocacy groups, politicians, just about anyone who found himself in the bad graces of the reigning government. Chief Justice John Marshall recognized this in McCulloch v. Maryland in 1819 when he wrote that the power to tax involves the power to destroy. No statement could more accurately describe the power of our Broadway Big Brother. When they say do not pass go! Go directly to jail, we know they mean business.