The figure of St Joseph is really a very interesting one not just in the Bible but also in iconography. Does iconography do justice with this central silent figure of God’s incarnation in history? Let us see the following examples of Christian art and iconography to try to answer this important question by seeing how our saint is depicted.

When one has a look at the mosaic decoration in the Basilica of St Mary Major, in Rome, which was completed between 432-440 AD. On the top register, one notices St Joseph to the right. In this mosaic, Joseph is young, bearded and garbed as a Roman of status as is appropriate to the consort of a queen. We see him conversing with the angels announcing Jesus’ birth and holding not a shepherd’s staff, but in his left hand a rod symbolizing the authority and responsibility he has just been given. In the bottom register, Joseph is on the left side, in Bethlehem, the city of David, the king from whose descendants, which go back to Joseph, Jesus was born.

From the mosaic decoration in St Mary’s Basilica in Rome we go to the Sinai Icon Collection. By looking at this icon, we are reminded that in the early centuries of Christianity, St Joseph appeared only in Nativity scenes. The obvious reason is that his presence within the Sacred Scripture is to be found practically there. The narratives we have of him which relate him to Jesus’ infancy are derived from Matthew’s Gospel as well as the Protoevangelium of James. Some of the existing images of Joseph can be found among the icons of St Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt’s Sinai. From these icons which go back to the 7th century, we find that Mary takes central stage with her Son infant Jesus. Angels, magi, shepherds, and maids serve Our Lord Jesus while musicians are playing. St Joseph is depicted in his characteristic pose, sitting in a corner of the cave, chin in hand, deeply reflecting what James calls Joseph’s Troubles. In other words, Joseph is aware of his wonderful and terrible responsibility regarding the care and protection of God’s incarnate as a human child.

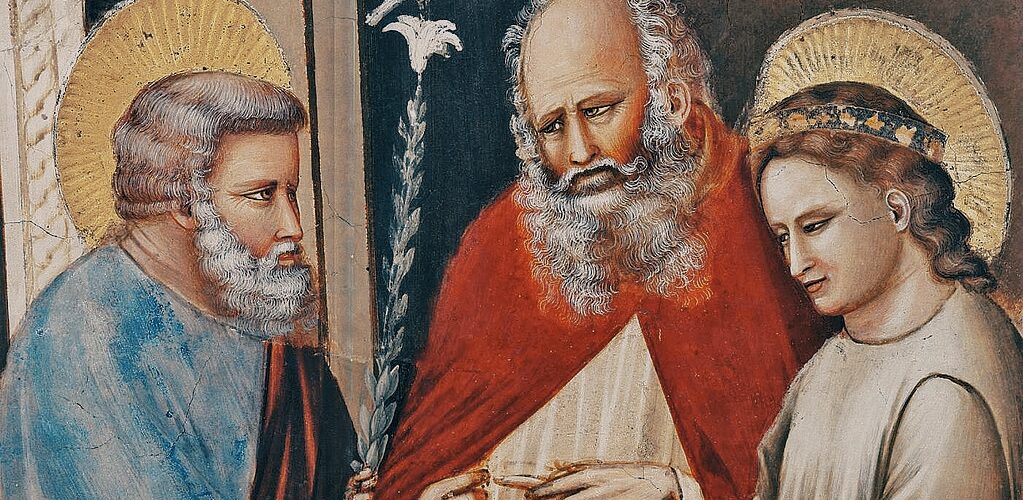

In the year 800, in France there is a strong interest in the details of St Joseph’s life which the Bible is certainly absolute silent about. Hence, in the 13th century, whilst Jacobus de Varagine collected myriad oral and apocryphal sources around the figure of Joseph with the Church’s tradition in work entitled Legenda Aurea or Legenda Santorum (The Golden Legend), the famous Porto-Renaissance artist, Giotto di Bondone (1305), managed to finish a huge cycle of frescoes on The Life of the Virgin For the Scrovegni Cappella in Padua. In his new lively realism as shown in his work Marriage of the Virgine, Giotto manifests to us an older St Joseph. The latter is old enough to be the guardian as well as the protector both for the Virgin and her divine Son. While presenting himself for marriage Joseph is presented carrying the rod. Here the rod has nothing to do with his authority but a witness to the events represented in the Legend account. Mary is the age of betrothal whereas an angel announced to the priest to gather marriageable men at the Temple with their rods. A divine sign was to be given to determine who is worthy to be betrothed to Mary. Obviously St Joseph was selected because a dove descended on his rod and a flower sprouted from it. It needs to be said that from this stage onward, most probably a lily started being a standard symbol of St Joseph in Church’s art.

Another interesting painting which undoubtedly gives us a deeper clue on the personality of St Joseph is the The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple by the Dominican friar Fra Angelico (ca 1540). As the medieval artistic world was waning, new paintings of St Joseph as well as of the Holy Family started to see the light. With the great Dominican painter, Guido di Pietro, commonly known as Fra Angelico, we get artistic depictions which left a powerful and lasting impression thanks to the warm and direct effect of these frescoes. In The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple fresco which was painted for the Dominican convent of San Marco in Florence, when the same friar was prior, namely between 1540 and 1542, we find a serene and warm tones together with an earthly backing devoid of golden embellishments. Most probably the scene depicted was precisely that of Fra Angelico for the aim of contemplation. In this scene, St Joseph is placed on the same visual plain as The Virgin. In this way the viewer immediately gets the clue that both figures are husband and wife. Mary is presenting her Son to Joseph as the latter is presenting the usual offering. One cannot say that Joseph is old nor young however he is an appropriate compliment to Mary. Moreover, the image of Joseph looks like other works of Fra Angelico that are self-portraits, hence showing that this prior-artist must have sought the patronage and example as he fulfilled his duties as Dominican brother.

From these three works of art one can frankly say that some of St Joseph’s iconography does depict the fact that he is close to us, humans. Like us, human beings, Joseph took the authority and responsibility which God gave him, of both his Son and the Mother of his Son. These works of art also inform us that Joseph not only did not take his mission lightly but was well aware of the great and terrible responsibility he had to the care and protection of God’s incarnate Son as a human child. The symbols attached to him tend more and more to show his interior spiritual beauty beautifully displayed in the virtues he heroically lived, particularly his industriousness, humility, chastity, listening, faithfulness to God and his family, discernment and taking bold decisions for the welfare of his family as a responsible husband together with being a putative, foster and an adoptive father. In all this St Joseph is an example to be imitated.

Ite ad Joseph! Go to Joseph!